In their book ‘African Political Systems,’ M. Fortes and Evans Pritchard (1940) conducted a comparative analysis of political behaviour. They employed an anthropological approach to assess the political systems of traditional societies, categorizing them into two groups: those with centralized states and those without – State and Stateless societies (Political Anthropology). These two terms are often used interchangeably: ‘cephalous’ and ‘acephalous,’ derived from the Greek word meaning ‘without a head,’ to describe societies.

State Societies

In this societal model, power is concentrated within a specialized mechanism. This applies universally to all tribal groups, regardless of their geographical extent. The role of a political leader in such societies is to establish laws, resolve disputes and levy taxes on these groups. State societies are characterized by:

- Centralized authority: Typically, a king or chief represents the entire society.

- Administrative organization: Various units handle administrative tasks, including tax collection and mediation between the government and the people.

- Judicial body: Responsible for interpreting laws, enforcing them and ensuring justice.

- The distribution of wealth and status is based on an individual’s power and authority, granting them specific social standing and privileges. Rulers, often kings or chiefs, hold high positions in the hierarchy.

The distinction between state and stateless political systems is based on several fundamental factors, including population, territory and economy, as well as the presence or absence of:

Judicial and legislative subsystems.

Mechanisms for rule enforcement.

Fiscal subsystems.

Stateless Societies

These societies are defined by the absence of a centralized and easily identifiable authority structure. Instead, functions are dispersed among several recognized individuals, with no one inherently superior; they are typically considered ‘first among equals.’

Stateless societies can be categorized into four main types:

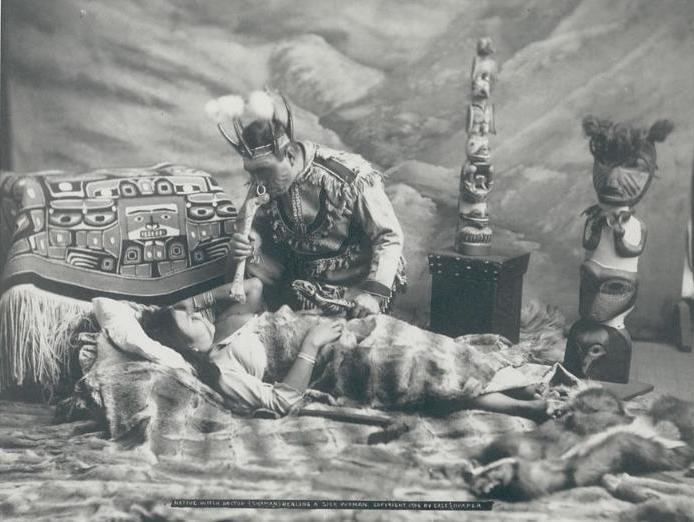

- As described by Evans Pritchard, the first category typically includes organized communities that rely on food gathering and hunting. They often live in small bands where authority primarily rests with the eldest member. Chiefs in such societies hold limited authority. Each band has its own territory where they can move freely. The leader is chosen based on personal qualities, characteristics, bravery and behaviour. They are responsible for the well-being of the band and are regarded as symbolic patrons of both the band’s welfare and territory. Examples of such societies include the Bushmen in South Africa, as well as certain communities in Southeast Asia, such as the Jarawa people of the Andaman Islands.

- The second category encompasses societies consisting of multiple rural communities. These villages are interconnected through economic and kinship bonds. Each village has its own formally elected council for local administration, but there is no overall chief for the entire society. Membership in these councils is determined by various factors such as a person’s popularity, wealth, capabilities and qualifications. Examples of such societies include the Ibo and Yako peoples of West Africa.

- In the third type, societies organized around age sets follow this pattern – Various age groups are established to handle all kinds of political and obligatory duties based on a person’s age. In these societies, decisions are consistently made collectively rather than by the elders alone. Each individual belongs to a specific age set and can be a member of only one. Interestingly, the age set system is also observed in state societies. An illustration of this type of society can be seen in the Nuer people of Africa.

- In the fourth type of society, authority is dispersed across numerous entities, which are further divided into various groups. In this setup, no single individual holds recognition as the head of the society. Gerontocracy, where the elderly hold power, is limited in this context. These groups become active, particularly in cases of blood feuds, but otherwise, they often exhibit opposition to each other. To address local needs and issues, the entire society is segmented into multi-level aggregate groups that differ in their roles, geographical areas and populations. Consequently, the entire tribe is subdivided into numerous segments, giving rise to a segmentary system. Examples of such societies include the Nuer and the Dinka of Southern Sudan.

Therefore, based on the preceding discussion, we can conclude that every society, whether within a state or a stateless setting, employs distinct systems to manage law and order. The disparities between state and stateless societies pertain more to their organizational structures than their functional aspects. This dichotomy represents two extremes, and any given social system may fall anywhere along this spectrum.

References

Polity – State and Stateless societies, forms of Government Law- UGC

STATELESS SOCIETIES- egyankosh

1 Comment

My Homepage

4 months ago… [Trackback]

[…] Read More Infos here: anthromania.com/2023/08/25/state-and-stateless-societies-political-anthropology/ […]