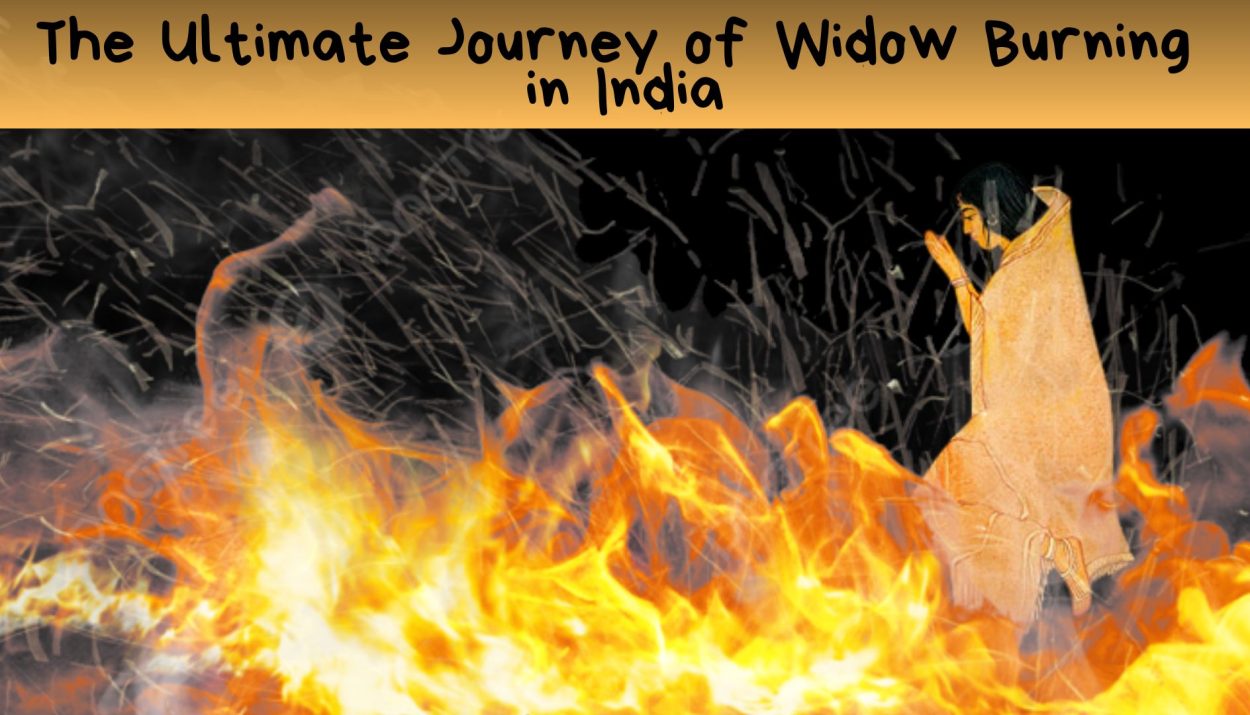

In the rich tapestry of India’s intricate cultural history, certain practices have left profound imprints, capturing global fascination and horror alike. Widow burning, also known as Sati (or Suttee), is one such practice. Here, we delve deep into this ancient tradition, tracing its historical roots, deciphering its social implications, and following the ultimate journey of widow burning in India through the annals of time.

This custom involves the immolation of a widow alongside her deceased husband’s funeral pyre. Many Hindu women regarded fire as a sacred element and viewed Sati as a solemn duty due to their religious scriptures’ promise of an afterlife in Heaven, where they would reunite with their husbands.

Initially, Sati was predominantly observed among women. Later, the practice of Sati spread among many castes and across every social level, chosen by or for both uneducated and the highest-ranking women of the times. The core belief underlying Sati was that a widow’s self-immolation symbolized the ultimate sacrifice and unwavering devotion to her husband.

The Historical Origins

The origins of the Sati practice remain the subject of ongoing debate. Historical records first mention Sati during the Gupta Empire era, approximately between 320 and 550 CE. In sacred texts such as the Mahabharata, Puranas, and Vedas, we encounter depictions of women practising Sati. The term ‘Sati’ itself means ‘virtuous woman’ and was initially associated with voluntary self-immolation by widows, expressing their devotion to their late spouses.

Some women even embraced self-immolation before their husbands’ expected deaths in battle, a practice known as “Jauhar.” Rajput Hindu women would perform this act following their defeat in battle. This act represented a profound form of self-sacrifice, aimed at safeguarding their dignity and evading capture as prisoners of war.

While voluntary Sati existed, historical accounts also recount instances of coerced Sati, where widows were compelled into the practice. The possibility of a widow remarrying after her husband’s demise was extremely rare, reinforcing the expectation that even young widows would end their own lives. Following self-immolation, a memorial stone and, at times, a shrine was erected in her honour, and she was revered as a deity. Examples of such Sati stones can be found in coastal Andhra and specific regions of Central India, predominantly dating back to the 14th century CE during the Vijayanagar period.

At times, Sati is associated with Hindu mythology, where she is depicted as the first wife of Lord Shiva. In this myth, her father’s strong disapproval of her marriage to Shiva drove her to self-immolate in protest against her father’s hatred for her husband. Her unwavering prayers during this challenging period eventually led to her rebirth as Parvati. It’s important to note that this narrative is largely distinct from the historical Sati practice, as Sati was not a widow when she chose self-immolation.

Read- Kailash Parvat: the mystery goes on!

The Ritualized Practice

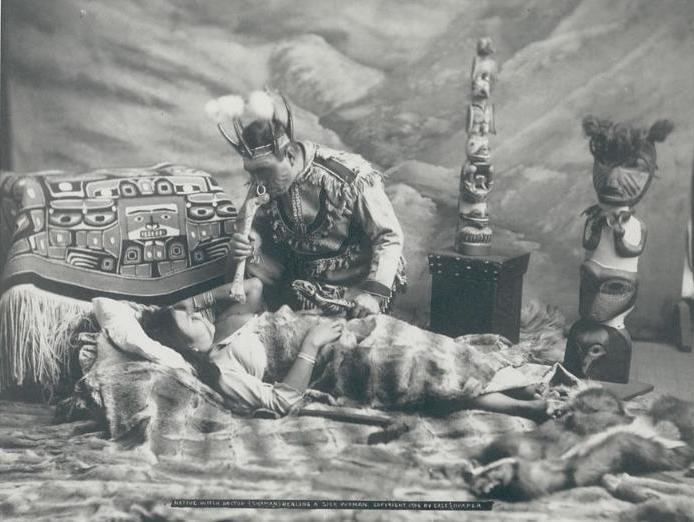

Numerous narratives shed light on the diverse methods used in conducting the Sati ritual. Many accounts depict women either seated on their husbands’ funeral pyres or lying beside the deceased. Some sources describe instances where women leapt or walked into the pyre once it was ignited. Furthermore, regional variations characterized the practice.

Sati was a highly ritualized ceremony. A widow would be adorned in bridal attire, sometimes drugged, and placed on her late husband’s funeral pyre. Often, the act was performed in front of a crowd, and there were even instances of royal patronage, legitimizing the practice within society.

Shifting Social Dynamics

Initially, the Sati system leaned toward voluntariness, but it later transformed into a mandatory practice enforced by the local populace rather than rulers. India underwent significant societal changes over the centuries, influenced by factors such as colonialism, social reform movements, and legislative alterations. The initial efforts to halt this inhumane tradition were undertaken by Muslim rulers in India, specifically the Mughals and Nizams. However, their attempts to abolish this practice faced widespread criticism and ultimately proved unsuccessful.

Figures like Raja Ram Mohan Roy and Ishwar Chandra Vidyasagar advocated for the abolition of Sati and played a crucial role in bringing about change. In the 19th century, Raja Ram Mohan Roy emerged as a prominent advocate against the Sati system, casteism, child marriage, and polygamy. He championed the cause of allowing widows to remarry. While the British initially tolerated Sati, it was first banned in Calcutta in 1798. Nevertheless, the practice persisted in neighbouring regions. Roy’s efforts drew the attention of Lord William Bentinck, then the Governor-General of British India, leading to the implementation of the Bengal Sati Regulation or Regulation XVII in 1829. This landmark regulation officially prohibited Sati and imposed legal consequences for those who practised it, extending the ban across the entire Bengal Presidency.

The British Raj played a pivotal role in eradicating the practice, as evidenced by the Bengal Sati Regulation Act of 1829. This was followed by the enactment of various anti-Sati laws across India, which criminalized both the act of coercing widows into Sati and those who facilitated it. Despite the ban in 1829, records indicate numerous official Sati cases each year afterwards.

At present, the Commission of Sati (Prevention) Act, 1987 aims to combat the harmful practices of Sati in India. This act is designed to enhance the prevention of Sati and the glorification of such acts, along with addressing related matters and incidental issues.

The Social Impact

The abolition of Sati elicited mixed reactions. While it was seen as a progressive step toward women’s rights and human dignity, some segments of society defended the practice as a matter of tradition and honour. Even today, debates surrounding cultural relativism and the influence of colonial intervention persist.

Sati was seen as a demonstration of a woman’s devotion and commitment to her husband. It had deep cultural and religious roots in certain regions, and for some, it was considered a virtuous act. The practice put immense social pressure on women to conform to societal expectations. It created an environment where women felt compelled to undergo Sati to avoid shame or dishonour. It perpetuated the notion that a woman’s identity and worth were linked to her husband.

It deprived women of their fundamental right to life and the autonomy to shape their own futures. Widows faced social ostracism and were regarded as symbols of misfortune within their communities. The practice of Sati frequently found religious justifications, portraying it as a means for a widow to achieve salvation and reunite with her husband in the afterlife. Nonetheless, this religious rationale often served as a guise, concealing the true motivations behind the practice.

Despite being outlawed, the legacy of widow burning continues to shape India’s cultural landscape. Some communities still venerate women who committed Sati as martyrs, and there are temples dedicated to Sati, regarded as sites of spiritual significance.

Conclusion

The journey of widow burning in India unfolds as a transformation, from a deeply entrenched cultural practice to a forbidden relic of the past. Though it has largely faded into history, the echoes of Sati continue to resonate in India’s complex socio-cultural fabric. Understanding this ultimate journey is crucial for comprehending the intricate interplay of tradition, colonialism, and social change that has shaped modern India. The legacy of Sati endures as India navigates its historical past while forging a path towards a more equitable future.

References

THE COMMISSION OF SATI (PREVENTION) ACT, 1987

‘Sati’ and the role of the state in India

The abolished ‘Sati Pratha’: Lesser-known facts on the banned practice

SATI: THE WIDOW-BURNING CULTURE IN INDIA

Sati Pratha: Widow Burning in India

Introduction to the Custom of Sati